On Early Intervention

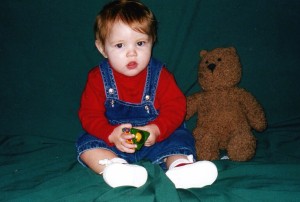

When Schuyler was born fourteen years ago, she was (perhaps irresponsibly) placed into the hands of two people who lacked even the most basic experience with a baby. To make matters worse, at least one of those people was an idiot. (SPOILER: It was me.) I shouldn’t admit how many times I looked at Schuyler and simply said to myself, “Oh my god, I have a baby and she’s still alive. This is one lucky damn baby.”

When Schuyler was born fourteen years ago, she was (perhaps irresponsibly) placed into the hands of two people who lacked even the most basic experience with a baby. To make matters worse, at least one of those people was an idiot. (SPOILER: It was me.) I shouldn’t admit how many times I looked at Schuyler and simply said to myself, “Oh my god, I have a baby and she’s still alive. This is one lucky damn baby.”

In a great many ways, Schuyler was very lucky indeed, even after she won the polymicrogyria lottery. Mostly, she was lucky because my work environment afforded her the resources of the Yale University School of Medicine. This was especially important after about eighteen months, when the search for an answer to her speechlessness had begun, almost entirely due to the careful attention paid by her Yale pediatrician.

Yale wasn’t perfect; when she was three, the Child Studies Center diagnosed Schuyler with PDD-NOS, but to their credit, it was also a Yale neurologist who immediately expressed dissatisfaction with that diagnosis and pursued the correct answer six months later. Schuyler spent those early years being closely monitored by literally some of the smartest people in the world. Given the subtlety of her polymicrogyria’s manifestation, it could have been years before she received a correct diagnosis, if in fact she ever did, without the access to the level of early intervention and big medical brains that she had. As I said, for a kid with a rare brain malformation, Schuyler’s a pretty lucky kid. She had smart eyes on her at a time when she very much needed them.

When we talk about identifying early developmental milestones in kids, especially those with special needs that aren’t obvious or easily identifiable, it can be an uncomfortable discussion. I think that’s largely because those conversations tend to happen outside a professional environment. I never really ran with parent-centric circles when Schuyler was very young, so I probably missed the worst of those little playground, play-date chats. I sat through enough of them to know how much they can suck the life out of a parent, though, especially one for whom a child’s differences are gradually revealing themselves. It can be pretty debilitating, listening to the comparative achievements of other people’s kids as they hit developmental milestones that your own child is missing. I can still remember some of those conversations from the past decade.

But as parents, we need to power through that emotional bog. We need to put our kids in front of intelligent people who know what to watch for. More importantly, we need to educate ourselves as to what we should be watching for. Every child is different, of course, and we need to be aware of our kids’ specific developmental needs. In that respect, knowledge is indeed power. Awareness of the subtle nuances of your child’s development can be the key to early identification and intervention.

Outside of the Yale Med School, Schuyler was also assisted by Connecticut’s Birth-to-Three program. She was helped by some very dedicated people who worked very closely with her, and by the time Schuyler was diagnosed, she was already accustomed to the kind of developmental therapies that she would ultimately require for the next decade of her life.

These early intervention programs are often woefully under-supported by their communities, and yet they are vital to the future success of our kids. They help parents get the information they need and inform them what to expect from the process. Doctors get data that helps them determine what to look for, something that was crucial in Schuyler’s complicated journey towards a diagnosis and subsequent therapeutic regimen. Schools benefit greatly as well, receiving guidance to develop appropriate instruction for special needs kids from the very beginning.

If you’re looking for more information on early intervention and developmental milestones, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is a good place to start. This was something of a surprise to me, actually. I always think of the CDC as a place where doctors do creepy things to monkeys and chase epidemics through third world countries. But as I said before, I’m not too smart.

Schuyler benefitted from the care and observation of some very smart people from a very early age. She continues to do so now. Schuyler is lucky, yes, but her luck has been largely powered by the benefits of early intervention. For that, her dumb, lucky father will always be grateful.

Note: To support the site we make money on some products, product categories and services that we talk about on this website through affiliate relationships with the merchants in question. We get a small commission on sales of those products.That in no way affects our opinions of those products and services.

Early intervention is SO important, not just for the kiddo but for the parents. Our time in it taught me as much as it helped her. That’s how it’s supposed to work. Then it changes…. Therapy comes from school and private sources. But parents also need to be aware that therapy comes from other daily activities, too! And it never stops. Trust me. My special needs kiddo is 18yo and still gets therapy daily just by living life!

EI was also crucial for my son’s (HOH, Aspie, Dev delayed…) development from 2-3yo. He went from basically being non-verbal to signing and having some speech by 3yo. It gave him tools he needed to start his IEP pre-school program. And the way the therapists therapy was play-based so he had fun and enjoyed his time with them. I can’t say enough about the experience.